I didn’t know a hybrid sedan could take a corner that fast. We were sitting in the car, adjacent to the runway where NASA’s ER-2 high-altitude aircraft was about to land. Tim Williams – an ER-2 pilot who will fly later this campaign – was driving, poised to speed down the runway after the plane, in case his fellow pilot needed help avoiding obstacles and gauging conditions.

And as soon as the sleek ER-2 came into view and descended over the runway, we were off. Williams hit the gas (battery?) on the hybrid and swung onto the runway, sending me and my video camera flailing against the passenger-side door as the aircraft buzzed overhead. We raced down the runway, chasing after the plane as it landed, balanced on its two wheels.

On board the ER-2 is MABEL – the Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar – a laser altimeter that is gathering data for the ICESat-2 mission. Wednesday’s flight was the first science flight of MABEL’s summer campaign to measure summer sea ice, land ice and more in Alaska.

The day started with a crew and weather briefing at 7 a.m., where pilots Denis Steele and Williams reviewed weather conditions and possible routes with ER-2 Mission Manager Tim Moes, NASA Goddard scientists Thorsten Markus and Kelly Brunt, weather forecasters and others.

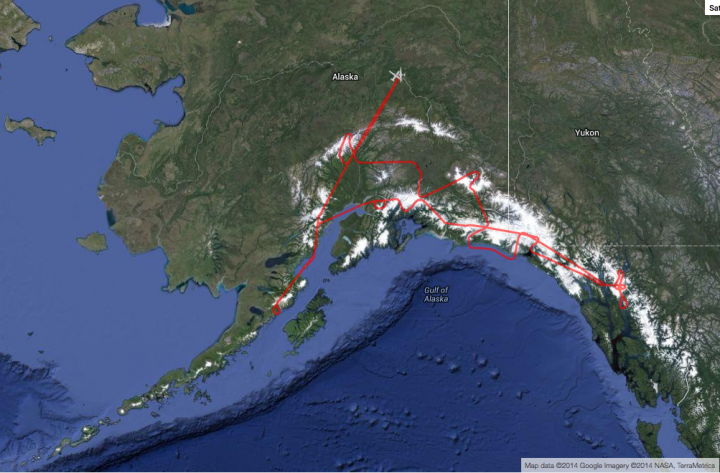

With cloudy conditions on the way to the North Pole – covering the dynamic melting edge of the sea ice the campaign hopes to document – the team decided to head southeast out of Fairbanks. That route heads down to the Alaska Peninsula to survey volcanoes, then heads east over glaciers and high-elevation ice fields in south central to southeastern Alaska.

The ER-2, with MABEL on board, flew over volcanoes and glaciers in south central and southeastern Alaska. (http://airbornescience.nasa.gov/tracker/)

With the flight route set, scientists made final checks of the instruments and Steele put on a pressurized suit – necessary for flying at 65,000 feet. He has to “pre-breathe” pure oxygen for an hour before flight, to raise his blood oxygen level.

Ryan Ragsdale, engineering technician, helps ER-2 pilot Denis Steele put on a pressurized suit before the flight, which will take him to 65,000 feet. (Credit: Valerie Casasanto/NASA)

Meanwhile, the plane was slowly towed out of the hangar onto the runway at Fort Wainwright and fueled up. The ER-2 crew and Williams went through the preflight checklist, which would be difficult for Steele as the pressurized suit has big gloves and limited dexterity.

ER-2s Denis Steele, in the cockpit, and Tim Williams, checking notes, get ready for the day’s flight. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

After Steele got in and started the engines, he taxied to the end of the runway accompanied by a maintenance van and a chase car: the van so that the crew could grab the bright orange stabilizing wheels, which fall off during takeoff, and the chase car driven by Williams, who supports Steele as necessary.

The ER-2 takes off amazingly fast. One moment it’s at the end of the runway, the next, the roar of the engine sounds. Then, all of a sudden, the aircraft’s in the air, climbing fast to the clouds. The plane disappeared into the clouds before the sound faded, and then the team went back to check the instruments’ vital signs, transmitted from flight.

Just under seven hours later, after flying over a number of key glacier and volcano points north of the Gulf of Alaska, Steele landed the plane. The crew reattached the bright orange stabilizing wheels, and towed him back to the hangar, where scientists were eager to download and view the data.

Steele reported on highlights of the flight – what was cloudy, what was clear – and Moes ended with a reminder of the next early morning meeting to review weather conditions and determine whether the ER-2 would fly another route over Alaska today.

Thanks for the great pictures of my nephew, Denis F. Steele. Please keep them coming.c